Lambdas

This chapter covers lambdas. You will learn the following:

What is a C++ lambda expression?

What are the parts of a lambda?

How can a lambda expression be used in C++ code?

Introduction

C++ lambda expression — often called a lambda — allows us to define anonymous function objects (functors) which can be used inline or passed as an argument. This was introduced in C++11 as a more convenient and concise way for creating anonymous functors. Let's take a look at a few simple lambda examples:

// Simple lambda printing string

[] { std::cout << "Simple lambda\n"; };

// Simple lambda returning sum of two elements

auto lambda_sum = [](int x, int y){ return x + y; };

// Simple lambda for sorting elements of the vector using std::sort

std::vector<int> vec{23, 1, 2, 44, 56, 37, 4, 9, 0};

std::sort(vec.begin(), vec.end(), [](int a, int b) { return a > b; });Parts of the Lambda Expression

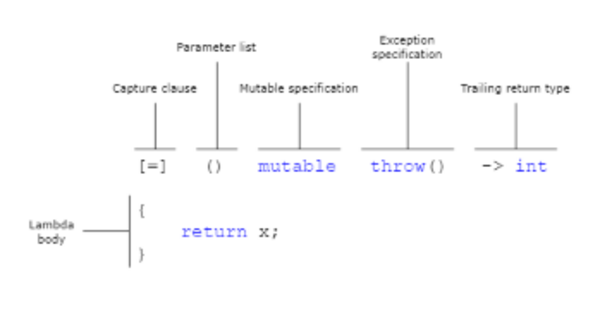

There are six basic parts of a lambda expression:

capture clause

parameter list — optional

mutable specification — optional

exception specification — optional

trailing-return-type — optional

lambda body

The image below shows them in a practical example.

Capture Clause

Capture clause is also called capture list or lambda-introducer. It is the beginning of the lambda expression. It specifies which variables are captured and whether the capture is by value or by reference. Examples of the capture clause are as follows:

[] — capture nothing

[=] — capture local objects like variables and parameters by value

[&] — capture local objects like variables and parameters by reference

[this] — capture this by reference

[a, &b] — capture objects a by value and b by reference

Let's see them in an example.

int number = 7;

// Lambda returning vale of number by using [=]

auto getNumber = [=] { return number; };

getNumber(); // returns 7

// Lambda returning sum of number and passed argument as a value by using [=]

auto addNumbers = [=](int y) { return number + y; };

addNumbers(6); // returns 13 (7+6=13)

// Lambda returning reference to the number by using [&]

auto getReference = [&]() -> int& { return number; };

getReference(); // returns int& to numberThere is also a feature called generalized capture. We can use this feature to introduce and initialize new variables in the capture clause, without the need to have those variables exist in the lambda function's enclosing scope. The type of the variable is deduced from the type produced by the expression. This feature is useful when we want to use it in lambda move-only variables from the surrounding scope:

auto ptr = std::make_unique<int>(8);

// Lambda using generalized capture

auto lambda = [capturedValue = std::move(ptr)] { /* use ptr*/ };Parameter List

Lambdas can capture variables and accept input parameters. A parameter list is optional and, in most aspects, resembles the parameter list for a function. Let's see the same simple code in a function form and as a lambda expression.

int add(int x, int y) {

return x + y;

}

auto lambdaAdd = [](int x, int y) { return x + y; };In lambdas, it's possible to use the auto keyword as the type specifier in a parameter list if the type is generic. It can also take another lambda expression as an argument.

auto lambdaAdd = [](auto x, auto y) { return x + y; };Mutable Specification

By default, value captures cannot be modified inside the lambda because the compiler-generated method is marked as const, but using the mutable keyword cancels this out. This means that the mutable specification enables the body of a lambda expression to modify variables that are captured by value.

int number = 7;

// number is reference, so the lambda modifies original

auto lambdaReference = [&number] { number = 2; };

// Error - lambda can perform const-only operations on number

auto lambdaValue = [number] { number = 2; };

// Due to usage of mutable lambda can modify number

auto lambdaMutable = [number] () mutable { number = 2; };Exception Specification

You can specify that the lambda will not throw any exception using the noexcept keyword. You can see what will happen if you compile and run the following code:

[]() noexcept { throw 13; } ;Most C++ compilers should show the warning during compilation, but other than that, the code will not throw the exception.

Return Type

In general, the returned type of the lambda expression is automatically deduced and there is no need to use the auto keyword for that, as shown below:

[]() { std::cout << "Sample output.\n"; }; // deduced type of the lambda is voidYou can specify trailing-return-type, which resembles the return-type part of the standard function. But please remember that it must follow the parameter list (even if it is empty) and you must use the -> keyword before the return-type.

// lambda returning int as trailing-return-type specifies

[]() -> int { return 13; };You can omit the return-type part of a lambda expression if the lambda body contains just one return statement or if the expression doesn't return a value.

// lambda returning int as deduced type from the single return statement

[](int x) { return x; }(7);Lambda Body

Because the lambda expression is the same as an ordinary function, its body can contain anything that's allowed in a function body. This means that a lambda body, similar to a function body, can access the following:

Captured variables from the enclosing scope

Parameter

Locally declared variables

Class data members (when lambda is declared inside a class and this is captured)

Variables with static storage duration (like global variables)

Let's look at a code example. We would like to print the elements of the declared vector together with information that includes whether the number is even or odd. The vector declaration is as follows:

std::vector<int> v {1, 2, 3, 4};Now, we can prepare the function printing number and the phrase "is even" or "is odd."

// lambda returning int as deduced type from the single return statement

void isEvenOrOdd(int n){

std::cout << n;

if (n % 2 == 0) {

std::cout << " is even\n";

} else {

std::cout << " is odd\n";

}

}To apply this function to all vector elements, we are using the for_each function from the algorithms library.

for_each(v.begin(), v.end(), isEvenOrOdd);The same result can be achieved by using a lambda expression instead of the isEvenOrOdd function:

for_each(v.begin(), v.end(), [](int n) {

std::cout << n;

if (n % 2 == 0) {

std::cout << " is even\n";

} else {

std::cout << " is odd\n";

}

});As you can see, there are no limitations related to the size of the lambda. The only limit may be the readability of the code, as lambdas are typically used as small helper functions.